As acknowledged, the pre-Roman Italian peninsula was home to a multitude of Native European tribes. Some of them were Hellenes, others, like the Ambrones, were Germans. There were also Celts, Etruscans and a multitude of tribes classified as Italic. The Italic tribes, unlike the Romans, whose legacy of oppression and subjugation has largely obliterated the traces of native Italic culture, were pure Europeans and their languages clustered close to Celtic, but with considerable Hellenic and, in some cases Germanic, influence. For example, the Germanic influence in Umbrian was so heavy that the first Umbrian inscriptions were held to be written in a Low German dialect, because of the many Germanic loanwords. Conversely, the Lucani or the Brutii had languages with predominant Hellenic influences.

In this article, I will examine the so-called North Picene language, mainly because it is said to be undeciphered and because of its relatively early attestation. The corpus of inscriptions classified as North Picene is very small, consisting of only four inscriptions, of which only one (the famous Novilara stele) contains a substantial text. Nonetheless, it is worthy to study those inscriptions and see what they shall yield, not only in terms of language analysis, but also in terms of explaining the symbolic narratives embedded in the inscriptions. One of the inscriptions (the one found in Pesaro) is later than the others, dating from the era of the forcible romanisation, hence why it contains a Latin part, with the same meaning as the “North Picene” one. But, let us begin from the earliest example, the Novilara stele, which dates from the sixth century BCE.

The transliteration of the text should flow like this: “mimniś erút gaareśtadeś rotnem úvlin partenúś polem iśairon tet śút tratneši krúviś tenag trút ipiem rotneš lútúiś θalú iśperion vúlteś rotem teú aiten tašúr śoter merpon kalatneniś vilatoś paten arn úiś baleś tenag andś et šút lakút treten teletaú nem polem tišú śotriś eúś”

Let us now try to interpret this arguably very confusing text.

“Mimniś” is a shortened form of the Greek imperative “memniso”, meaning “remember”. “Erut” sounds like the Greek future tense “ero” of the verb “lego”, which is unrelated to the Latin “lego”, but means “to speak”. So, the first two words mean: “remember what I shall say”, which is a typical formulaic beginning of funerary texts.

“Gaarestades” is a contracted form of another typical phrase in such a context, namely of the phrase “egaresen Hades”, meaning “so spake Hades”. Here, Hades assumes the role of “narrator”, he who shall inform the descendant of the deeds of his ancestor, whom he revives. Arguably, in the context of such rituals, Hades was impersonated by the midwife of the mind, the Pagan priest.

“Rotnem” looks like an accusative case, combining the Old English (thus Germanic) word “rood” and the Hellenic suffix that forms the accusative. “Rood” means “wood, grove” and the next word, “uvlin”, has the same meaning, since it is an adjective, the Hellenic “ulinon”, meaning “from the wood of a sacred tree”. So, this phrase means “near the sacred grove”. The twofold repetition of the same meaning is common in such epitaphs, adding emphasis to the sacral meaning of the text. “Partenus”, from Greek “parthenos”, means “untouched”, denoting the grove itself, untouched by man.

“Polem” comes from Greek “polis”, meaning “dwelling, settlement”. “Isairon” is cognate with Old English “isern”, meaning “iron”. The phrase should be understood as “the dwelling of the iron-clad ones”, which means the necropolis, where the warriors are interred. “Tet sut” is a condensed form of “tetta suto”, meaning “so far he lay”, an indication that the person he speaks of is dead.

The phrase “tratneši kruvis” should better be read with restoration of some missing vowels, becoming “tera tina si kruvis”, which, in Dorian Greek, would mean “the earth-born is here hidden”. The “earth-born” is the deceased, the ancestor about to be revived.

The next phrase, “tenag trut ipiem rotnes lutuis” means “Tenagos is pressed by the wooden plank in the burial ground”. Tenagos, the name or appellation of the deceased, actually means “dwelling in the darkness”. “Trut” is from Greek “trutos”, meaning “pressed”, “ipiem” from “ipos”, meaning “plank, wooden slab”, which refers to the coffin housing the body. “Rotnem” we have already explained and “lutuis” comes from the Minoan word “lyttos”, meaning “mortuary temple, barrow”.

The phrase “θalú isperion vultes rotem teu aisen tasur” translates us “the flower of the nobles, his likeness preserved in wooden image, for all the tribe to praise”. More specifically, “θalú” comes from “thallos”, meaning “flower”. “Isperion” is a Dorian isogloss of “Hyperion”, meaning “above all, wonderful”, here denoting a nobleman. “Vultes” is an Osco-Umbrian cognate with Etruscan “voltu-“, which was borrowed also in Latin as “vultus”, meaning “face, likeness”. “Rotem” is like “rotnem”. “Teu” is from Germanic “theod-“, meaning “the tribe”. “Aisen” is the future tense of the Greek verb “ado”, meaning “to sing, to commemorate by praise”. “Tasur” comes from “tassomai”, meaning “to be arranged like that”. This part of the inscription tells us that the deceased was an important nobleman, whose tribe commemorated his memory.

Subsequently, we have the phrase “Soter Merpon Kalatnenis vilatos paten arn uis”, which means “The preserver, bull-roaring, fair cutter of the bounds, horse-rider, shall tread on the man’s sacred spot”. “Soter”, literally “preserver”, is the descendant, who will preserve the honour and accumulated hamingja of the kin by reincarnating his ancestor. “Merpon” is a compound word, from PIE *meros, meaning “bull” (as evidenced in the name of the Frankish King Merovech, whose name means “sacred bull”. “Kalatnenis” is a compound word, formed from “kalos”, meaning “fair of visage” and “toneia”, meaning “cutting of the bonds”. “Vilatos” is the word “ilatos”, preserving the archaic phoneme of the digamma, transcribed with the letter v, meaning “leader of the ile (cavalry formation)”. “Paten” stems from the verb “pato”, meaning “to step on”. “Arn” is a contracted form of “arsen”, meaning “man” and “vis” is a cognate with Gothic *weiha, meaning “sacred”, here denoting the sacred spot, the grave. The part about the bull alludes to the symbolism of the bull as the life-force of the ancestor, which passes to the descendant. The cutting of the bonds is the severing of the umbilical cord and the part about the riding of the horse alludes to the fetus “riding” the placenta. The “stepping on the grave” is the descent of the initiate, the reincarnation ritual in itself.

The text continues with the phrase “bales Tenag ands et sut”, meaning “the fixed-in-place darkness-dweller will be unfastened and shall move”. “Bales” comes from the verb “ballo”, which means “to fix in place”. “Ands” stems from “anadeo”, meaning “to unfasten”, while “sut” is from “seiomai”, meaning “to quake, to move”. The passage is a clear reference to reincarnation.

The last part of the text is the phrase “lakut treten teletaú, nem polem tisu sotris eus”, which translates as “he shall speak in the third ritual, hailed by the community as the good preserver (of the ancestral glory)”. “Lakut” stems from “lacto”, a shortened form of “ylakto”, meaning “to shout”. “Treten” is easily recognisable as meaning “third” and “teleta” is the Greek word for “ritual”. All the other words we have already explained, save for “tisu”, stemming from “tiomai”, meaning “to be honoured”. So, the reborn man, who has gone through the reincarnation rites, will be acclaimed by the tribe.

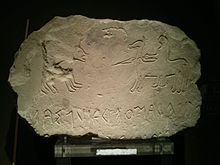

As we can see, the symbolism manifests on all images, as we see hunting images, men with spears, and such. Similar depictions we find on Pictish stones, as well, thus bearing testament to how connected and quintessentially identical the art of the Native Europeans is. Now, however, let us see the other, far shorter, North Picene inscriptions. Of them, only the second, dated shortly after the first, has an accompanying image.

The text reads “t ip edam o edai up bal”. If one adds the missing vowels, the phrase reads as: “ton ippon edama o edai upo balous”, which, in Dorian Greek, means “I tamed the horse, as it should, with an pointy weapon”. Of course, the text is symbolic. The unnamed speaker is the fetus/initiate, the horse that is “tamed” is the placenta (“ridden” by the fetus) and the pointy weapon is the umbilical cord. The accompanying image bears the very same symbolism as the short text. The inscription dates from the second half of the sixth century BCE.

The third inscription is fragmentary. The only salvageable portion of the text reads “lupes…. Mre geer”. If we follow the patterns we used until now then lupes corresponds to Greek “lupisas”, meaning “saddened”. Alternatively, it can be connected to the Etruscan “lupo”, meaning “wolf”, which entered Latin as a loanword. “Mre” maybe stands for “moros”, meaning “death” and “geer” for “geron”, meaning “old man”, or possibly it can be cognate with Old High German Ger-, meaning “spear”, from Proto-Germanic *gaisa. In any case, the inscription surely has a religious/sacral connotation, as such its ultimate meaning surely refers to reincarnation. The inscription dates from the fifth century BCE.

The fourth and final inscription is much later, dating after 200 BCE and is bilingual, as already stated. The non-Latin part of the inscription reads: “Cafates larth laris netsvis trutnut frontag”. The translation should proceed like this: “Cafates, the ancestral spirit, the ancestral spirit, in the underground sacred spot presses the thunderbolt”. Cafates is the name of the ancestor. “Lar” is an Italic word meaning “ancestral spirit”. It derives from Greek, and its literal meaning in that language is “inside the pit”, referring to the grave. As we have seen, the repetition of the lexical item gives a further sacral connotation. “Netsvis”, I speculate, is a compound word from “nerteros”, meaning “of the earth, chthonic” and the “-vis” part from *weiha, meaning “sacred”, as we saw with the first inscription. “Trutnut” is similar to “trut”, which we also saw in the first inscription. “Frontag” derives from Greek “bronte”, meaning “thunderbolt”. So, the meaning is that the ancestor lies in the grave, waiting to be revived by his future incarnation, who shall revive his life-force, symbolised by the thunderbolt, same, in fact, as the wheel depiction we saw in the Novilara stele, which also occurs throughout Cisalpine Gaul (Northern Italy).

So, those were the four inscriptions in the North Picene language. As this article demonstrated, the language contains mostly Hellenic elements, but Germanic features are also strong, while Italic and Etruscan influence is considerably smaller. So, we could perhaps classify North Picene as an idiosyncratic Hellenic dialect, which, because of proximity to the Ambrones and the Etruscans, was influenced by their languages. In this respect, itcis markedly different from its closest neighbour, namely South Picene, where Italic influences predominate. The exact point where speakers of North Picene gave way to speakers of South Picene is unknown and it is possible that the two languages were spoken, more or less, in the same area, although it is doubted that they were mutually intelligible. Unknown also is when exactly North Picene ceased to be spoken, fully suppressed by the Latin language, which the Romans forced upon the indigenous European peoples whom they subjugated. Most likely, the Romanisation of Picenum had been finished in the decades following the death of Augustus, since, after the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, nothing suggests the survival of any pre-Roman language of Italy, save for Greek and maybe Camunian, which however is completely unattested, so its status cannot be determined. Unfortunately, North Picene never yielded any literary texts and no lexicographer did (or maybe was forbidden to) compile further lists of its vocabulary.

Nonetheless, the precise classification notwithstanding, something inferred, of equal importance, is how the inscriptions have a deep symbolic meaning, referring to reincarnation. Once more, it is shown how the interpretation of European mythology, ritual and tradition by Varg Vikernes and Marie Cachet is entirely correct and how it can unlock and render clear all the riddles crafted by our ancestors. It is because of their phenomenal and groundbreaking tapping into the wisdom of the ForeBears that the interpretations you see in this article became possible, so it should only be fair to end this with a statement that everything correct in this article should be credited to them, whereas anything wrong is the fault of the author alone.